[ad_1]

by Anna Boyles

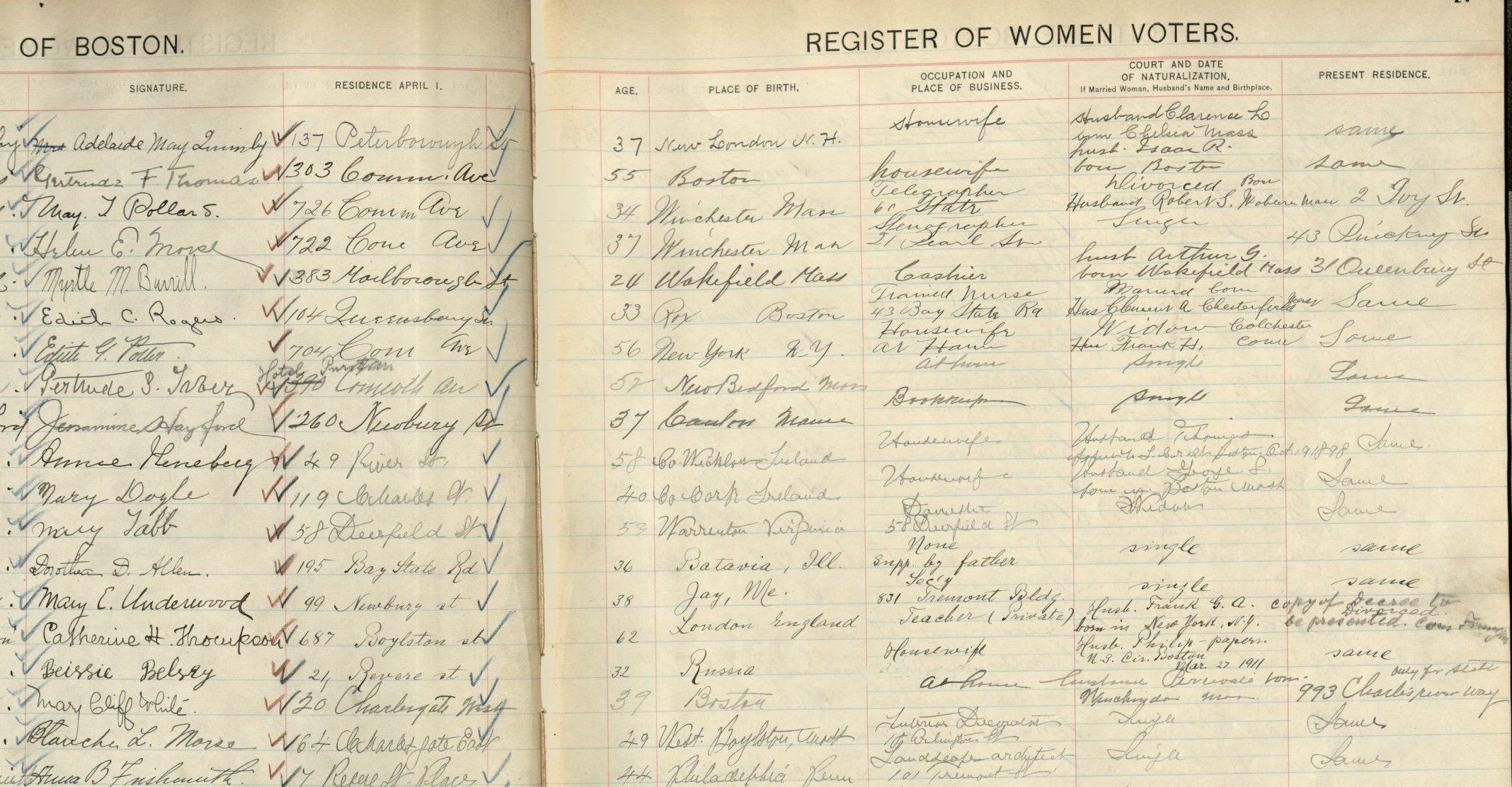

In the 1910s and 1920s Boston, one would have been met with a dizzying number of rental options. The city’s women’s voter registrations from the fall of 1920 reflect Boston’s diverse housing at that time, showing how some chose not to follow the traditional expectation that women should live at home with family.

One respectable option for a single woman at the time would be to rent a room in an individual’s home. If many people also rented rooms in that home, it would have been known as a boarding house or rooming house. Rental arrangements may or may not have included cleaning services and meals. Living with a private family or in boarding houses had been popular with unmarried working women for decades, but by 1920, urban women in the professions were instead attracted to a newer option known as the apartment hotel. Catering to primarily middle and upper-class residents, these apartment hotels were multistory buildings which provided rooms and amenities to both permanent and transient residents.

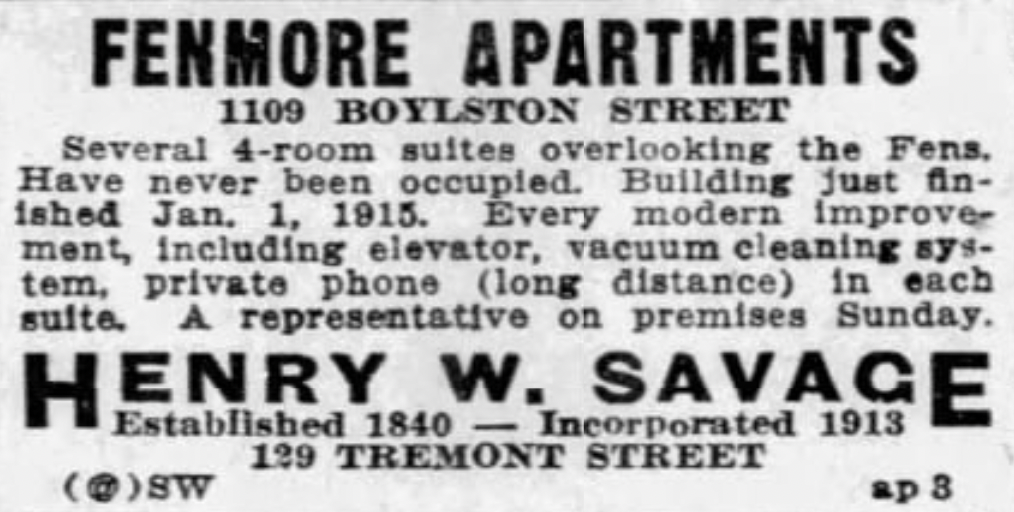

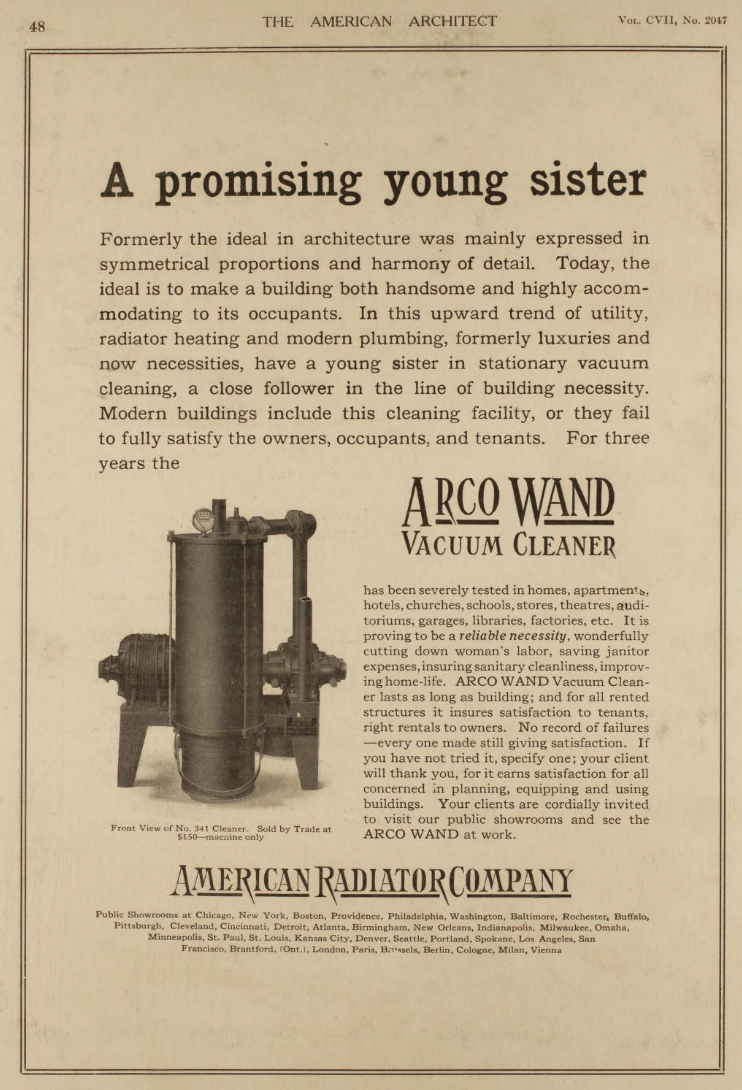

The Fenmore Apartments, a complex of seven buildings on the corner of Charlesgate East and Boylston Streets, was built in 1914. It joined several other apartment hotels built in the Fenway neighborhood during the first two decades of the twentieth century. Amid the World Series celebrations at nearby Fenway Park that autumn, the five-story apartment hotel was hurriedly preparing to welcome its first residents: single women, men, and small families. In addition to breakfast and linen service, the Fenmore’s two-hundred-plus renters could take advantage of modern conveniences such as elevators, long-distance telephones, and an electric vacuum cleaning system known as the Arco Wand. The Fenmore employed its own fireman and an employee to tend each building’s coal-fired boiler.

The construction of the Fenmore, and the dozens of other apartment hotels in the Back Bay and the Fenway, could only be possible after the city undertook a large infrastructure project to fill in the swampy marshland adjacent to the Charles River. In order to create land where there previously was none, the city filled the area in with gravel hauled in from neighboring towns. Although this project began in the 1850s, the Fenway was not open for development until around 1900. It was at this time that landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted designed the restoration of marshland, transforming the area into the winding tree-lined parkland known as the Fens.

One early resident of the Fenway, James McKenzie, recalled when the area was covered with wild shrubbery that attracted birds and bird watchers alike. At age ninety-eight, McKenzie told those recording his oral history that as he regularly walked through the neighborhood around 1906 to visit his girlfriend who studied at Simmons College: “But I used to walk over to Simmons to see Gertrude and at that time, none of these buildings was up. And I used to see pheasants going across the road over to the field . . . . [T]hey hadn’t built the Wentworth School or any of that stuff there, then. And they stood out like a sore thumb, Simmon did. With that little green roof and it was a small building then, it wasn’t what it is now.” Other Fenway neighbors remembered in oral histories how popular the neighborhood was not only for college students but also for both musicians and professors: “I remember most of the symphony players used to live around here . . . . And there were many teachers, many music teachers. You would hear good music coming from every window. Somebody was playing the piano or practicing voice or playing the violin. There used to be a number of professional people here, college professors.”

The Mary Eliza Project transcription team so far has located forty-five women who lived at the Fenmore and who registered to vote following the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, the majority of whom were independent working women. New women voters at the Fenmore Apartments were employed as physicians, nurses, teachers, office workers, and indeed, musicians and professors.

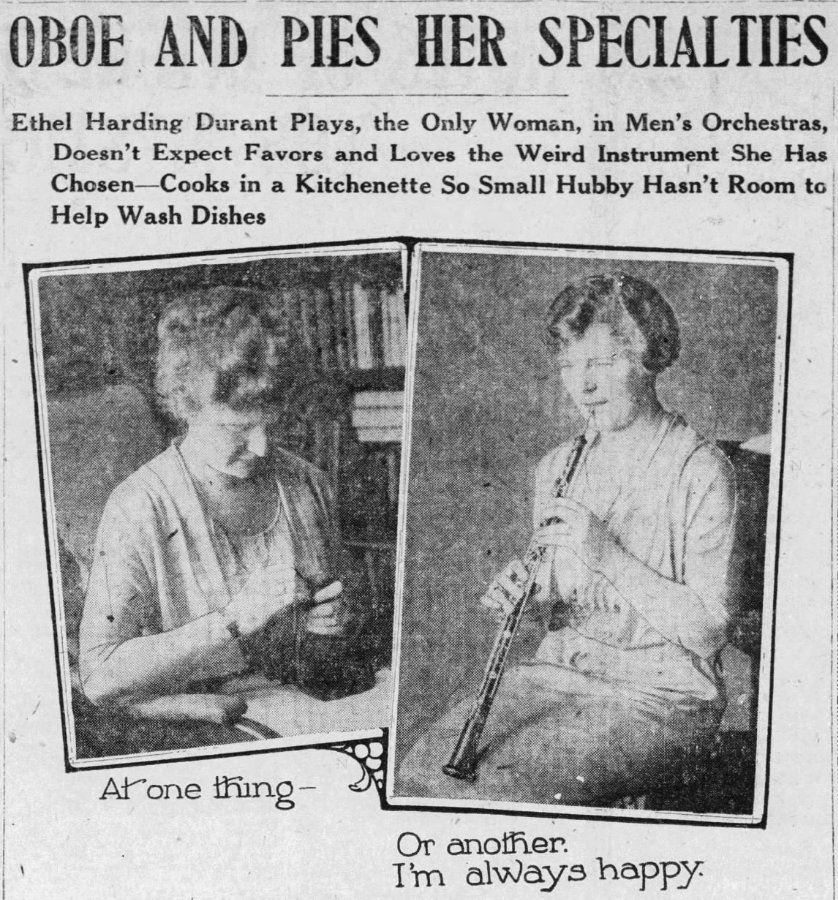

Ethel Harding, for example, was thirty-three years old and a musician when she registered to vote in October 1920. At the time she rented a room at 1111 Boylston Street, part of the Fenmore. The Boston Globe published an article featuring her in 1922; the piece suggests that Harding may have been one of the first women to play with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. A concert pianist, Harding studied at the New England Conservatory of Music and under Marie Dewing Faelton, the president of the Professional Women’s Club. Harding additionally played the oboe, English horn, and alto oboe, and had been able to support herself financially since she was just sixteen years old.

Two professors at nearby Simmons College and long-time residents of the Fenmore Apartments registered to vote in 1920. Amy Maria Sacker moved into the Fenmore as early as 1916 and was living with her mother at 64 Charlesgate East when the two registered to vote in October of 1920. At the time, she was forty-eight years old and employed as an artist, according to the register. Sacker was professionally employed as book cover designer and illustrator, and she taught at both her own design school and at Simmons College. She began instructing young women at Simmons in 1904, teaching design and interior decoration courses as part of their Household Economics program. Amy Maria Sacker lived at the Fenmore for nearly fifty-years, making the large apartment hotel her home from 1916 until her death in 1965.

Sacker’s co-worker and neighbor at the Fenmore, Blanche L. Morse also registered to vote in October 1920. Morse was employed as an interior designer, and she also taught in Simmons College’s household economics program. After graduating from Smith College in 1892, Morse studied at Sacker’s design school. As well as owning her own interior design firm, Morse was employed by both Simmons College and Sacker’s design school. Blanche L. Morse remained a resident of the Fenmore Apartments until her death in 1938.

The business model of the Fenmore and other apartment hotels attracted busy working women who desired first-class services and amenities but who may not have been able to afford to employ their own servants. Apartment hotels furthermore provided single women more autonomy than afforded by boarding houses and private homes, whose owners were known to enforce strict rules on female residents’ behavior. It is not surprising, then, that women who claimed their right to vote would desire the greater independence of living in an apartment hotel, rather than in more of a family setting. Nearly fifty women at the Fenmore registered to vote in 1920, as well as dozens more at the Hotel Vendome, Hotel Touraine, Hotel Buckminster, and others. Explore our dataset and discover the variety of residences, including apartment hotels, in which Boston’s new voters lived.

Read more:

“A Hotel of Her Own: Building By and for the New Woman, 1900-1930,” Nikki Mandel

The South End’s Franklin Square House: Working Women Claim the Vote in 1920

Suffrage at Heart: The Women Artists of Boston’s Ward 8

Fenway Oral Histories, Boston City Archives

The Once and Future City: Fenway, Anne Whiston Spirn, MIT School of Architecture and Planning

Anna Boyles is a dual-degree student in History and Archives Management at Simmons University.

[ad_2]

Source link